SO. I’ve been a bad nature guide recently.

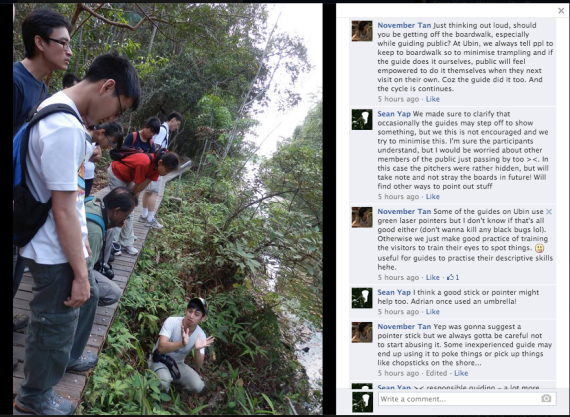

At Macritchie’s Prunus trail, I stepped off the boardwalk in excitement to show the participants a pitcher plant. Thankfully, after the photo was posted, I was promptly reminded by more experienced guides November and Ria as they alerted me to my erroneous ways, for which I apologise. Not all is negative though, this has been a good learning experience!

At the start of the walk we did emphasise to the participants not to stray from the path or boardwalk, though the guides may sometimes do so in order to show them certain things. On hindsight, I realise that this should NOT be the case – the guides should not leave the trail either!

This is for a number of reasons, apart from the most important reason of possibly adversely impacting the very things we are trying to show to others. Partly, it is because while we trust our participants to understand, the trail is public and other trail walkers may see these acts and assume they too can do the same. Mostly, however, the guides should never put themselves in a situation where they seem to be “higher” than the participants, or above any rule or guideline that they themselves have set for the participants.

Quoting Ria Tan’s guide to guiding,

“While guides may say “It’s OK for a guide to do this but you shouldn’t do it”, generally visitors will do as guides DO and not as guides SAY. Just imagine every visitor doing exactly what you are doing the next time they are on the shores alone. You can then have a clear idea of the appropriate behaviour to take when guiding.”

While this was written in the context of a shore walk, it applies to terrestrial – no – actually all nature walks too!

Anyway, this incident has prompted me to reflect on my guiding experiences, and though I have made mistakes there are some useful tips I have learnt as well.

I’m talking to myself here, but if you’re a budding guide you can imagine I’m talking to you too I s’pose.

Things to change

- STAY ON TRAIL! And practise only responsible behaviour – never do anything you don’t want to see others doing, and the walk is about the flora and fauna, not you (the guide) – care for them comes first.

- Hold back on the jargon! It may not be intentional, but do get to know layman terms and descriptions. For example, this actual conversation:

“Oh look, a Tenebrionid (darkling beetle)!”

“Uh, english please?”

Sometimes, I find myself stuck in situations where I only know the scientific names, which are more often than not NOT relatable at all. Not trying to boast here, this can be a real problem – in guiding, common names are definitely more useful in introducing an organism or feature, as they are commonly (pun possibly intended) physical descriptions of a trait of that organism. And also in english, which is understood by most people, unlike latin. For example, Lathrecista asiatica may sound nice and fancy, but the only thing people can get from that is “Oh it’s probably found in Asia.”Instead, why not try:

“This is a fine example of a Scarlet Grenadier, which belongs to a group of dragonflies known as the Grenadiers, so named for their red, blue and yellow colouration being similar to the uniforms of the grenadier soldier specialization of the past. This species gets the Scarlet in its name from its striking red abdomen, which also gave rise to its other common name – the Asiatic Blood Tail.”This can further go on to interesting tidbits of information such as how many insects, especially the butterflies, have common names reflecting something to do with the military, because the first people who named them were the colonial troops who arrived in the past. It could also possibly lead into how many odonates (dragonflies and damselflies) have very fancy common names such as the Shadowdancer, the Fiery Gem and the Emperor!

Scientific names can also be introduced though, if they translate to something useful such as how most species of ladybirds have their number of spots reflected in their latin name (E.g. Henosepilachna vigintioctopunctata, vigintioctopunctata = 28-spotted).

- Do not treat animals as trophies – e.g. taking photos with sea stars, holding them up away from the water. Guilty of having done this before too. Sometimes the novelty of seeing an organism not commonly seen gets to us, and we want to take pictures with it to show friends (fuelled by self-gratification, of course. Refer to the first point!). This sends the wrong message and encourages disrespectful treatement of the shores – anyway a not so good photo of an animal or plant in its natural state is worth so much more than a good photo of one removed from it.

- Know your content well, and do not be afraid to admit you may not have all the answers.

Sometimes, I find myself blurting information, and thinking “Wait, where did I hear this from? Is it credible?”

If you have an interesting fact that you think you know, make sure to check for accuracy and reliability of sources! Not saying anything is better than spreading false information. If you DO mention information like this, do also clarify that you may not be 100% certain of its validity! You can though, recommend search terms or sources to go to should the participant want more information! Or even better – if you have a smartphone, check for validity on the spot! Which leads to my next point.

Tips I’ve learnt

- Technology! Use it! With the incredible miracle that is 3/4G, having a smartphone (with a data plan) can be very useful when guiding.

Hear a bird call but cannot see it, and don’t have a guidebook on hand? Consult Google Images!

Trying to describe certain behaviour that cannot be observed at the moment? All hail YouTube!

While guiding yesterday I was trying to describe the appearance and behaviour of a little-known group of insects known as Web Spinners (Embioptera), and thankfully there was sufficient network coverage and we were able to listen to our virtual guest guide David Attenborough talk about these wonderful little creatures with the accompaniment of video clips, all thanks to the power of YouTube.

In any case, never try to force a hiding animal out, or force an organism to exhibit certain behaviour. Use a guidebook or the internet to help illustrate your point.

- It helps to know your audience, and gauge their reactions. Test the water at the beginning of the walk! Find that the participants respond better at the mention of food and edibility? Capitalise on that (but be sure to clarify that poaching and hunting is illegal and greatly discouraged)!

I find that with teens and young adults, linking stuff to popular media such as games or movies is very helpful and keeping their attention. Comparing the burrows of tarantulas to Shelob (from the LOTR franchise) or Aragog’s (from the Harry Potter series) lair, or talking about how certain organisms inspired cartoon or game characters, like how the design of the Pokemon Victreebel was based on real life pitcher plants.

- Use analogy to relate the subject to something more human or to do with everyday life. Sex and relationships are bestsellers. The life cycle of the fig wasp can be described as a tragic love story – “After emerging from the pupa, the mature male’s first act is to mate with a female. The males of most fig wasp species lack wings and are unable to survive outside the fig for a sustained period of time. Once mated, the males begin to dig out of the fig, creating a tunnel through which the females can leave. Once out of the fig, the male wasps quickly die – some never even make it out, living their short lives without ever seeing the light of day.”

In the sex lives of insects there are also stories about traumatic insemination, but you’re free to read that one on your own heh.

As guides we are not all perfect, and we’re all bound to make mistakes (some more than others ><), but I feel what’s most important is that we learn from our mistakes and from each other!

For more information about how to be a better guide, Ria has many useful pages on WildSingapore that are very helpful:

So remember! The good guides always win (people over)!

Posted by Ria Tan on March 2, 2014 at 8:35 am

Thank you Sean for this great reflection! And for the important point about using technology. I’ve ripped off this key point for the wildsingapore pages on guiding tips.

I made a lot a lot of guiding mistakes. In fact, many of the tips are based on my personal mistakes! The important thing is to learn and share; and that’s what you’ve done. Thank you!

Posted by yongy on March 2, 2014 at 1:43 pm

nice one la sean